Sweeping through my draft on the first run, I want to make sure that my story says and does what I want it to say and do. If it’s a comedy, it has to be funny. If it’s adventure, the scenery, characters and places must be vivid. If it’s philosophical, the message should be presented in a manner that allows thought and reflection.

I began developing this ‘sweeping’ process after my first book, where I was editing sitting in front of the computer, trying to get it all done in one go. Save time and effort and all of that. Now, knowing what I know now, I wish I had done it all in sweeps instead. I tried to fell a forest with a pocketknife, then wondered why it was so hard and took so bloody long.

Now I see it as a progression: From the lumberjack and sawmill, through the planer and woodstore, then to the whittler and his knife. Apply the appropriate methodology at each stage, and all of a sudden it ain’t so bad.

My current set of sweeps is broken into three parts: Story, Language and Correctness.

Story

What do I mean by Story? I mean sensibility, continuity, characters, premise and enjoyability – the overall book from start to finish ignoring the finer details. Does it have a beginning? Does it have an end? Does it do what it’s supposed to do?

Does the story make sense? Your audience makes a commitment to reading your book: They promise to read it and enjoy it if, and only if, you meet them half way. Underwriting fiction is the whole concept of suspension of disbelief. The audience will let things slide, and for the most part forgive bad grammar and structure and just about everything else, if you don’t take the piss:

“Shmuck Dodgers, on the verge of defeat with no possibility escape, took from his boot the Atomic Disencrackenator that he had forgotten about until just now and with a push of the button zapped the bad guy into oblivion.”

“Jason, I know you cheated on me with my best friend, burnt my house down, tried to kill me, but I love you anyway!”

“Faced between saving her family or losing her million dollar career, Gillian called upon the spirits of her ancestors to create a doppelganger robot for her that would stand in her place at work while she sorted things out at home.”

Of course, fiction is fiction, it’s not supposed to be ‘real’ in the perfect sense. Cool. But there’s a limit. You can tell when an author is squeezing for an out. Case in point: A Princess of Mars. Toward the end, with a couple of pages to go, you get to thinking “How is he going to wrap this up? There’s nowhere else for this to go, unless…”

Boom, there’s a throwback to a random bit in the middle that smells suspiciously like Edgar had to work it back in to give himself an out at the end. The rest of the story was alright, but the sense of ‘oh, crud, I’ve got to end this…’ comes right through and ruins the romp.

If the story doesn’t make sense, the audience will be annoyed and they won’t come back. Even if your book is supposed to be quirky, there is a limit to what is quirky, and what is just nonsense.

Be your Audience

In the first sweep, make sure you look at the manuscript with fresh, critical eyes. To help with that, leave the book alone for a fortnight. Forget about it. Calm your nerves, be disciplined and go onto something else (hey, isn’t it time you designed your front cover, anyway?).

You’ll be surprised how strange your book looks when you’re disengaged. More than once I’ve caught myself thinking, “Heck, I wrote this?” as I flick through.

This was almost the case with Hampton Court Ghost, only I realised how putrid it was before I called it a draft. After I (heavily) altered the story, I did my sweeps just as I normally would – no shortcuts.

Because you’re looking down from such a high level (remember, you’re not doing grammar or punctuation or language just yet) you can also spot that if “Justin crawled out of bed and faced the morning traffic”, to have “Justin watched the shadows lengthen” doesn’t follow. The audience’s mental scene had a dawn going on, and then we’re asking them to make it evening all of a sudden.

Another example might be “Jo has curly blonde hair”. Later on we find her “Pushing her dark hair behind her ears…” and unless she coloured her hair somewhere through, the mental model of a character inside the audience’s head will flag up because it just doesn’t match.

And you’ve broken the flow, broken the illusion, broken the contract.

All of this means that you are watching out to make sure things happen in the right order, that there isn’t too much labouring on scenery or dialog, that characters are built, secrets are revealed, etc.

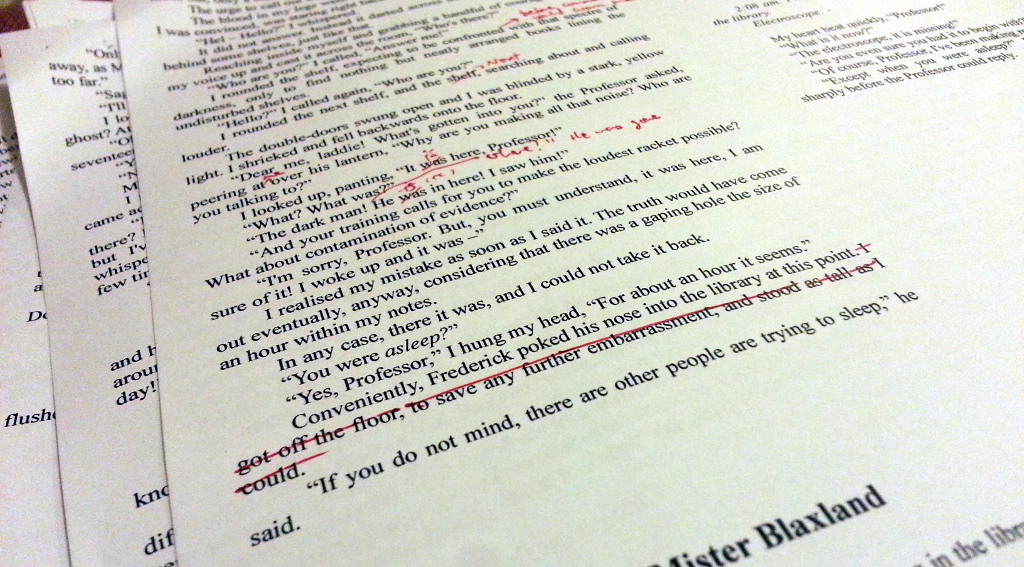

By the end of your first sweep, you should have big slabs of material move around, points to elaborate on, whole sentences and paragraphs to rip out. And don’t be afraid to rip stuff out. If something doesn’t work, or it smells funny, or it looks disjointed, it probably doesn’t belong.

How? Draw a big red line through it and look it over once you’ve finished. You’re more inclined to get rid of a stupid sentence if there’s a ruddy line running through the middle of it – yet another reason to use pen and paper.

Next I’ll be getting onto Language.

[…] to say, and it starts and ends properly. You’ve checked the continuity and all of that in the previous sweep, and you’ve made the appropriate corrections by moving slabs of text about or getting rid of […]