“What is this filth?” Nana exclaimed, hurriedly clapping the novel shut lest the foul contents should spill upon the floor. She looked up, “Who’s leaving this lying around? What sort of person gets his jollies writing this tosh?”

“Um. That’d be me.”

Awkward. Embarrassing. Demotivating. The conversation from this point can only go down, down through the maw of gall, past the spleen of shame, into the bowels of contempt. It’s a conversation – you know what? Make that plural: They are conversations that any entertainer or performer or writer is going to have to have at some stage with people they know.

Justification

I remember back in grade five, we were asked to draw a picture out of a squiggle. There were dragons and wizards and horses and cats. I managed to make a girl’s face out of mine, with long hair, a rounded chin and a scowl. I thought I did a pretty good job of it, I even added shading to give a sense of dimension and shadow.

“Why is she frowning?” the teacher asked, “She should be smiling.”

I shrugged, “She’s not happy.”

And then came all the questions. Rather than just a pat on the back, a grade out of ten and moving on, I spent the rest of the lesson (and some of recess, I remember distinctly) justifying what I had done. All because the face frowned. I don’t know if the teacher was just trying her hand at amateur psychoanalysis, but it really grated on me.

When I got it back home again, I put it in the bin. It was just another drawing, after all, doesn’t matter. But it did matter, clearly. It’s the things that matter that get stuck in one’s memory because these are what teach us our lessons.

It taught me that, even though there might not be anything technically wrong with a piece of art, it doesn’t mean that everyone (or anyone) is going to like it.

So how do you stop Granny from flicking through your horror-laden gore-fest?

Mitigate

You can’t stop her. Nor can you stop Bill, your turtle-neck wearing, self-appointed king of critics from reading and expressing his opinion on why your Cowboy should have been rougher. Nor can you prevent Jane, the innocent seventh-grader discovering the foul-language exchanged between the captain and her lieutenant.

The first thing you need to do is relax. People get it when a book isn’t for them. They’re a lot smarter than you think. No one is about to pick up Enid Blyton and complain about the lack of character development or the short, unsatisfying action scenes.

There is more to a book than just the story. In much the same way that people convey extra meaning to their words through body language and inflection, books have their own mechanisms for subtle suggestions.

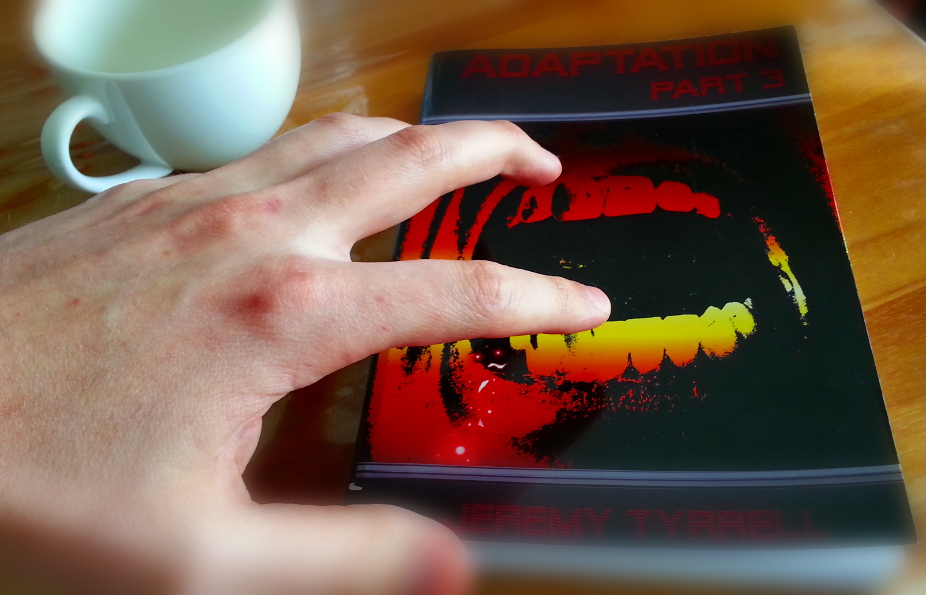

The front cover image is your first port of call. We all judge a book by its cover. It’s natural. I was looking at “The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” in print the other day. If, I challenged myself, I knew absolutely nothing about this book, would I even bother picking it up to read it? And the answer was “No, I would not.” The same goes for Shambleau.

Why? Because the covers didn’t appeal. Both are sci-fi, both are very good stories, but, if I solely based my selection on the covers, I would have passed them by. You can, and should, tailor your cover to reflect the contents and intent of the book. A goofy cover let’s Bill know that the text within is not meant to be taken too seriously. A dark cover shows little Sally that the contents might be spooky or dark.

The front cover, besides attracting your audience, lets them figure out for themselves whether they want to bother opening the book – give your audience the credit they deserve.

The next stop is the blurb and front matter. Nana might not have stopped at the front cover, but now she’s adjusting her spectacles and examining the back. By this stage, she should have a pretty clear idea that the book isn’t a Dick Francis mystery.

Hand in hand with the blurb is the actual language used within the book. Big words, long sentences, complex grammar; little Sally is bamboozled by the first page, so she puts it down and seeks something else. On the flip side, a children’s or teenager’s book might use simpler terms, snappier sentences, briefer descriptions. The natural attraction to or repulsion from vernacular means you, in a literal sense, let the words do the work.

One must not forget that there is the also actual format of the book. Books published electronically (eBooks) are filtered out by a user’s own preference. They can do it by genre, by keywords, and even with ‘safe search’. Today’s searchers give ‘you might also like…’ or ‘those who bought this also bought…’.

This means that those who want to read your tales of gangster ultra-violence and/or butter and porridge orgies will have everything working to this end and vice-versa.

Ultimately, short of hiding Nana’s reading glasses, there’s nothing you can do to actually prevent someone from reading your book, so the next best thing is to use your language and design skills to let the reader know what they’re getting themselves in for.

If, after a solid front cover, a proper blurb, appropriate language and categorisation Nana still balks at your book, Bill revs up his critical analysis, and Jane practices the new bad words she learnt, then so be it: You’ve done all you can to warn them, anything more is out of your control.

As an independent author, you strive to make your book as visible, as readable and as enjoyable as possible. The last thing you want to do is think of ways to stop people from reading your book.

It’s at this stage you, as an author, need to grow a thicker skin. More on that in another post.